This week’s field activity was a continuation of the last

three weeks field activities, which involved creating a navigational map,

learning to navigate using that map and a compass, and learning to navigate

using only a GPS unit. The purpose of this week’s field activity was to learn

how to navigate using a global positioning system (GPS) unit, with the ability

to rely on the maps we created. To do this each team was provided with the

landscape terrain maps they created (images 1 and 2). Our professor also

provided each person with a sheet of paper that contained a series of points,

which coincided with the points on our maps, which contained their latitude and

longitude (lat/long) coordinate locations (image 3). Every person was also

provided with GPS unit (image 4).

Image 1: Navigational

map of landscape terrain created in a previous week’s lab

Image 2: Reference

side of the navigation map created in a previous week’s lab

Image 3: Sheet

provided to us by our professor with the point’s coordinate location

Image 4: GPS unit used

for navigation

The catch with this week’s activity is that paintballing was

incorporated into it. We had used all the methods in the previous week’s

activities, and updated our maps to better assist us in the field. Because of

this we were very familiar with the tools we had to navigate with, the pros and

cons of each of them, and the landscape we were traversing. The purpose of the

paintballing was to add a little fun into the mix, and also to encourage us to

use our skills wisely and efficiently. The area we navigated had a total of 15

points we were instructed to locate. This time we didn’t have a specific course

to navigate through; all six teams simply navigated the points as they felt was

most efficient. Navigating from point to point involved matching the lat/long

location on the sheet of paper to the lat/long on the GPS unit (image 5).

Latitude measures your location north and south, while longitude measures

location east and west. Because of this a compass provided in the GPS came in

very handy (image 6). Navigating also involved reading the terrain of the

landscape we were traversing using our map’s contour lines.

Image 5: Location of

lat/long coordinates on the GPS unit

Image 6: Compass on

GPS used for traversing from point to point

As mentioned in the last two week’s activities, as well as

Field Activity #4: Distance and Azimuth Survey, before one can use a compass

they need to check the magnetic declination of the place they are using it at.

Magnetic declination is the angle between compass north and true north. Compass

north is the direction the north end of a compass needle points, while true

north is the direction along the earth's surface towards the geographic North

Pole. Magnetic declination varies both from place to place and with time. In

Field Activity #4 we established that the magnetic declination of Eau Claire,

WI was 0ᵒ 59’ W. Since 0ᵒ is such a small declination no adjustments to the

compass is necessary.

Location

The area where the navigation took place was located on the

outskirts of Eau Claire, WI at a place called The Priory (image 7). This land

parcel is owned by the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. This space is used

as the university day care center. Because of this restricted areas needed to

be added to our navigational maps. We needed to stay a safe distance away from

where the children utilize the area for safety reasons regarding them.

Image 7: Locational

map of the The Priory in Eau Claire, WI where the navigational activities take

place

Methods

Updating Our Maps

Before we could actually begin the navigation part of this

activity each group’s maps needed to be updated. This involved adding the course’s

navigation points and numbering them, and adding the no shooting zones feature

classes. We also needed to make corrections to our maps based on things that

could be improved upon to allow for more efficient navigating. Our group was

very happy with the first map we created so all we added was the labeled points

and the no shooting areas (images 8 and 9).

Image 8: Navigation

Map with the course’s navigation points labeled and the no shooting zones added

The red dots with a

number and letter above them represent the course’s navigation points and the

yellow zones represent the no shooting zones

Image 9: Reference Map

with the course’s navigation points labeled and the no shooting zones added

The red dots with a

number and letter above them represent the course’s navigation points and the

yellow zones represent the no shooting zones

Getting Ready For The Navigation

To begin this activity we had to haul all the equipment

(image 10), which included paintball guns, safety masks, and snow shoes, out to

The Priory. We then had to get all the equipment set up in an organized manner

(image 11 and 12). Getting the paintball

guns set up involved screwing all the pieces of the gun together and filling

the guns with paintballs (image 13).

Image 10: Truck used

to haul all the equipment out to The Priory

Image 11: Getting all

the paintball guns and safety glasses laid out in an organized manner

Image 12: Getting the

snow shoes out for everyone to take a pair

Image 13: Filling the

guns with paintballs

Each person then had to select a paintball gun, safety mask,

and pair of snow shoes (snow shoes were optional for whoever wanted to use

them) to use and get themselves prepared for the navigation (images 14 and 15).

Image 14: Getting snow

shoes on for whoever chose to wear them

Image 15: Set to

navigate with all the necessary equipment on

The Navigation

Before beginning the navigation each person needed to turn

on the track log on their GPS unit (image 16). Once the track log is turned on

the GPS unit begins tracking the route you walk. It is very important to turn

this on otherwise you will not end up with any data at the end of your

navigation to see how well you traversed from point to point using the lat/long

coordinates and your map.

Image 16: Location on

the GPS where the track log is turned on and off

To begin the navigation we all had to start from the same

starting point. At that time every team took a separate route of their choosing

to get to the first point they were navigating to. We were instructed we needed

to wait at least 5 minutes before any shooting began. This was intended for

safety reasons and to give each group time to separate from other groups and

actually focus on the navigation.

To locate the first point, our group agreed to traverse to,

we matched the GPS unit’s lat/long to the lat/long on the sheet of paper (image

17). We also used the map. By using the map we were able to match the elevation

we were starting at with the elevation of the first point we were navigating to

and use the 2-ft contour lines to determine how far down the hill we needed to

go. Using the map also useful because we were able to see which direction we

needed to go. By doing this we could

match the compass on the GPS unit with that direction. This was also an

efficient method because the lat/long and the compass are located on the same

screen on the GPS so you don’t have to switch between screens while navigating

(image 18).

Image 17: GPS unit

used to navigate from point to point by matching the lat/long to the sheet of

paper with lat/long coordinates for each point

Image 18: Lat/long

coordinates and compass located on same screen for more efficient tracking of

directional movement

Once a navigation point was reached (image 19) we used the

hole punch provided to punch the number point sheets that were provided to us

(images 20-22). We also took a way mark on our GPS unit’s.

Image 19: Point

marking the navigation courses

Image 20: Sheet

provided to us to punch with the hole punch once they were navigated to

Image 21: Sheet

provided to us to punch with the hole punch once they were navigated to

Image 22: Sheet

provided to us to punch with the hole punch once they were navigated to

We continued to navigate the course using this method until

class time was over. At this point we

headed by to the starting pint and turned our track logs off. It was important

to turn the track log off because otherwise anywhere you went after the

navigation activity was over would be recorded. This would make it extremely

difficult to know your course when the file was downloaded to the

computer.

Downloading The Data

Following the navigation activity we needed to get our track

logs and way points downloaded from our GPS units to a computer.

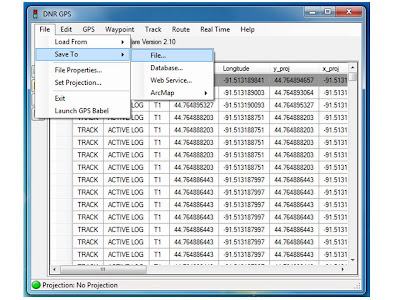

To do this I used a program called DNR GPS was that was

already installed on the computers (image 23).

Image 23: The DNR GPS

program used to download my track log points onto the computer

The following steps will lead you through the process that

was executed to get the data from my GPS unit onto the computer.

1. First,

the GPS unit needed to be connected to the computer with a USB port cord (image

24).

Image 24: GPS unit

connected to the computer with a USB port cord

2. Then, the “Track” tab was

selected (image 25).

Image 25 : “Track” tab selected

3. Next, the “Track” tab at the

top of the screen was selected and “Download” was chosen (image 26).

Image 26: “Download”

was chosen from the “Track” tab dropdown menu

4. Then,

the computer downloaded the track log data from the GPS unit (image 27).

Image 27: Computer

downloaded track log data from GPS unit

5. Next,

the data was saved into my personal class folder on the W drive as a point

shapefile (images 28 -30).

Image 28: “Save to”

then “File” is chosen from the “File” dropdown menu

Image 29: Navigate to

my class folder to save my data as an “ESRI Shapefile”

Image 30: Chose to

save my data as a “point” shapefile

After the track log was downloaded into my class folder I

created a geodatabase, in my class folder, using ArcCatalog. Here, I imported

my shapefile as feature class. Next, I brought my track log into ArcMap (image

31).

Image 31: Track log

brought into ArcMap as a point shapefile

After checking the projection of my track log I saw that is

was in GCS_WGS_1984 (image 32). It was projected in this coordinate system

because that’s what the GPS unit I was using was set up as.

Image 32: Track log

downloaded in a GCS_WGS_1984 coordinate system

However, the professor instructed us to have our track logs

projected in UTM Nad 83. So, I projected my track log into NAD 1983 UTM Zone

15N (images 33 and 34). This is because Eau Claire, WI is located in UTM Zone

15 North.

Image 33: Using the

toolbox in ArcMap to project my track log feature class into the correct

projection

Image 34: NAD 1983 UTM

Zone 15N as the chosen projection for my track log

Finally, I was able to bring my track log into a new blank

map in ArcMap (image 35). By doing this, the data frame for the map was set to

this projection due to project on the fly.

Image 35: My track log

after the projection

After getting my track log data download I needed to get my

way point data downloaded. To do this I followed the same steps as outlined

above, except selected the appropriate “Waypoint/s” tabs instead (image 36).

Image 36: “Waypoint/s”

tabs to be selected to download way point data

Now I was able to create maps that depicted the navigation

routes for myself, my group, and all groups combined.

Results

Map 1 depicts my individual track log. It shows that overall

navigation from point to point was a little curvy. I didn’t walk in a straight

line from point to point; however some were better than others. When comparing

my final navigation, using both a GPS unit and a map, to my second navigation

(map 2) of using only a GPS unit you can similarities in the curviness of my

routes.

Map 1: My individual

track route and way points from the final navigation activity using a GPS unit

and a map

Map 2: My individual

track route from the second navigation activity using only a GPS unit

Map 3 illustrates my groups track logs. Here we can see that

overall we followed similar paths. When comparing it to map 4 we can see that this

was also the same in comparison to our second navigation. However, there are

certain areas in our routes that show times when we split up slightly from one

another. This is most vivid in the patch of pine trees in the southwestern

section of the map. This is due to our group coming in contact with another

group and having a paintball war with one another.

Map 3: My groups track

routes and way points in relation to one another’s from the final navigation

activity using a GPS unit and a map

Map 4: My groups track

routes and way points in relation to one another’s from the second navigation

activity using only a GPS unit

Map 5 shows the routes for all 6 groups. Team’s routes and way points are depicted

through color coding. For example the same color genre from light to dark.

Overall, we can see that teams typically followed similar paths. This is the

same when compared to map 6.

Map 5: All six groups

track routes and way points in relation to each other from the final navigation

activity using a GPS unit and a map

Map 6: All six groups

track routes and way points in relation to each other from the second

navigation activity using only a GPS unit

Discussion

Overall, we can see similar patterns in how teams routes

overlapped one another’s in most cases. Clearly map 5 shows very unstable

routes in comparison to map 6. This is because there was no preset path or

course to follow. In comparison to the previous weeks routes I didn’t think that

the curviness of the paths differed too much. In all, we found the using the

map was helpful and found that we rarely used our GPS units at all.

By taking way points on our GPS units we were able to

compare them to the course navigation points that were given to us. By

comparing how the two lined up in relation to one another we were able to see

how technology is not always perfect. Needless to say we didn’t get to all of

the points in the time we were for this activity. Fifteen points was a lot to try to get to in

the spread out area we were navigating in 2.5 hours we had to collect them all.

Conclusion

From this activity I learned several important aspects

involving navigational skills, keys to success for future navigation, and the

pros and cons of the tools involved. Throughout all the navigational activities

we’ve conducted this semester I’ve learned the importance of team work. At

first working on a team to some may just seems nice to have others around to

visit with and make the time more enjoyable. To others who like working alone

it may seem annoying and stressful. But what I’ve learned from all these

experiences is that working in a team provided us with efficiency and success.

Our team worked very well together and everyone brought different strengths to

the board. This proved very helpful for certain aspects. For example, one of

our team members had very long legs and was good at keeping pace counts in the

deep snow. Another team member was very good at tacking locations using the

lat/long on the compass.

I also learned that’s it’s very important to be familiar

with the gear you are using in the field before going out and trying to

accomplish an important task with it. For example, my protective face mask kept

fogging up on me. This was extremely annoying, inefficient, and unsafe. I had

to keep stopping to take off my mask and wipe the clear area off I looked through.

This slowed us down and was very unsafe for in the event there may have been

another group around who may have started shooting at us. I also found the snow

shoes to pose difficulty. Overall, I thought walking through the snow in them

was much easier. However, I kept stepping on the backs of my own snow shoes

with the opposite foot and kept falling down. This slowed us down, tired me

out, and I kept smacking my shins on branches laying down under the snow. They

were also hard to maneuver quickly in. When another team was present and you

were trying to get low, hide behind a tree to position yourself in a safe place

to shoot at them it was very difficult to do because they were so large and

clunky. Finally, I found that the gun got very heavy at by the middle of the

navigation. Again, this made me tired and slowed me down. Next time I would

choose to put a stack on my gun so I could carry it over my shoulders.

Finally, I learned the importance and pros and cons off all

the navigational tools were used. I found that I liked using the map the best.

However, I can’t say that the map alone is sufficient. For the last navigation

activity we were pretty familiar with the landscape, since we had already

navigated two courses in previous weeks. The area was also fairly small, not

small in the sense that it was too small for this activity, just in the sense

that we could determine our placement on the course in relation to the

interstate and the day care center building. This made the last navigation

easier than the first two because we could look at the map, determine our

position, and remember the terrain of the landscape we were looking for to get

to our next way point. Not only that, but the 2-ft contour lines made it very

easy to determine ridges, valleys and flat areas. This was especially helpful

in reading the landscape. I found that I liked the first method of azimuth and

pace count, with the map the best. I thought using azimuth with the compass

made the direction we needed to travel very straight forward, and the pace

count worked well for determining distance. However, I do think that without

having my team members for pace count that I would’ve done as good, or been as

happy with the method. Again, this plays into the fact of the high snow and me

having short legs. I think that pace count would be much easier when there is

no snow on the ground. I also like the azimuth and pace count method because

technology can always fail you. So if you started off using a GPS unit and the

batteries died you could always rely on your never failing compass and pace

count. Overall, I found the GPS unit to be difficult to use alone without a

map. The second time we used it with the map it didn’t come in as handy as the

first week because we were familiar with the landscape and had our map. I think

the GPS unit and map together would complement one another very well in an

unknown landscape.